You don’t need to look to know it’s a hospital room – you can smell it. Lemon and linen and formaldehyde. If you do look, though, you’d find a room that looks exactly as it smells. Your eyes might hurt from all the gleaming white, sting of ammonia like staring directly into the sun – tile floors scrubbed clean, impeccable walls.

The nurses all wear white, cornsilk hair wrapped neatly at the napes of their necks, magazine cover smiles. I think there are four of them that rotate shifts, though honestly I’ve lost count. They appear three times a day with meals and twice to bathe me. Bath time is the best part of the day. It’s relief from the itching sheets, starched stiff, from the tied-too-tight medical gown that binds me in white. On good days, I even enjoy the feeling of rough sponge opening old scabs, though the blood dripped onto the floor is a violation to this temple. An unsmiling janitor in snow-white coveralls wipes it away before it has time to dry.

Friends, we made it. Welcome to the end. Or, if you’re new here, just welcome. You’ve reached the final stop on a months-long deep dive into how horror uses color. The good thing is, unlike a train, the final stop doesn’t signify the end. You can always feel to start back up at the beginning. If you want an overview of all the colors I cover in this series, please check out The Meaning of Color in Horror. Unless your favorite color is brown or a specific shade or something metallic, I’ve probably talked about it (and even something metallic isn’t necessarily a barrier – in my article about yellow, I get into the meaning of gold in horror). If there’s something you think I missed, please feel free to leave a comment with suggestions.

Anyway, that’s enough pontificating on a journey that I am sure has meant very little to you (to you, this is just me filling up space talking about writing instead of doing the writing). You’re here because you’re interested in the role the color white plays in horror.

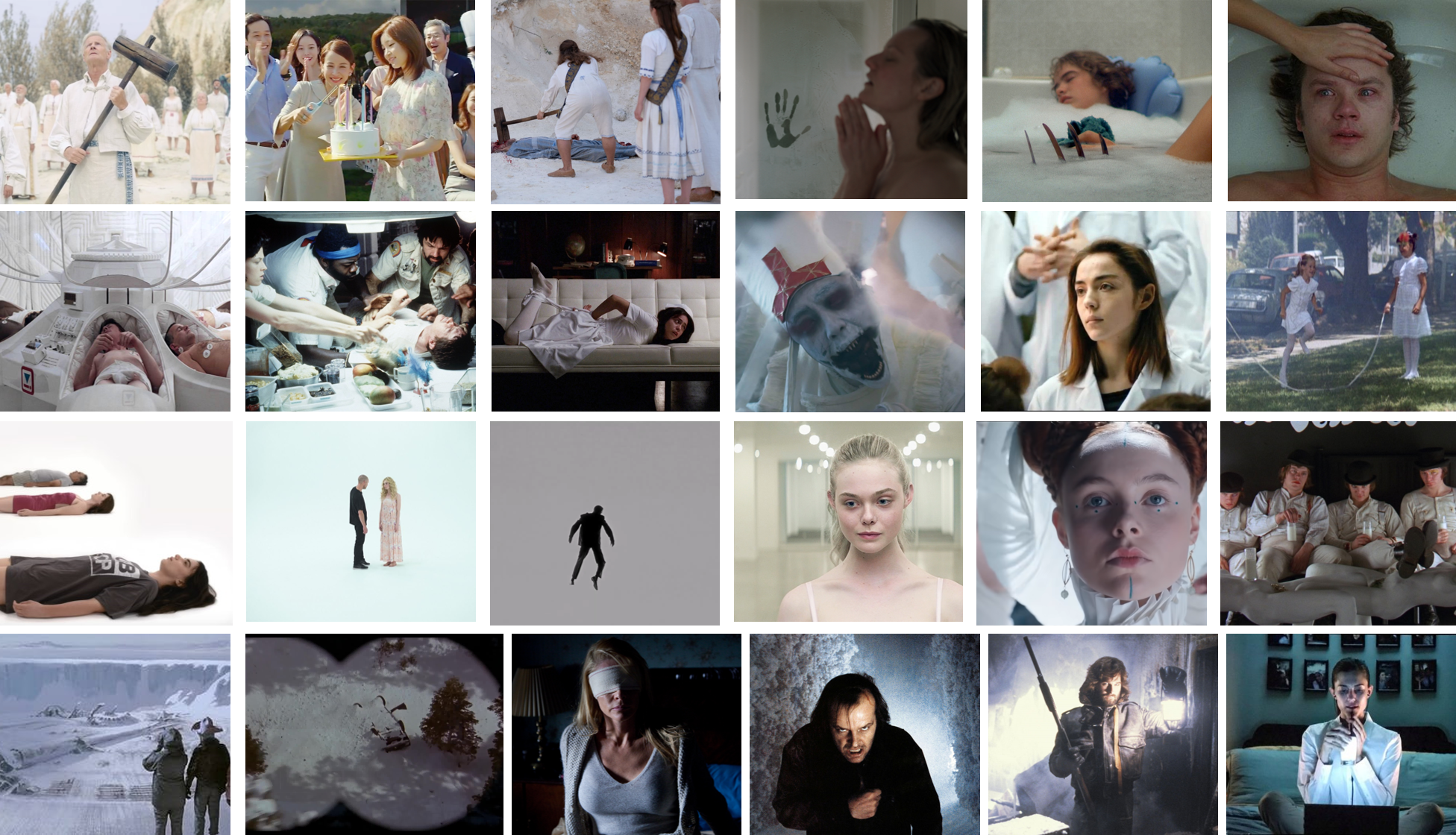

To be honest, I was shocked by how easy it was to find visual examples of white in horror. I legit thought that this would be the hardest color to find examples of. It’s the opposite of black, horror’s most iconic color. It’s all light and innocence. Sure, I figured, it’ll appear somewhere in horror; if I can find examples of pink and purple in horror, I can find white. But I didn’t think it would be easy. Boy, was I wrong. The first thing I did, before even writing a single word, was make a collage of examples for each color I wanted to cover. For the collage dedicated to white, I ended up finding so many examples, that I eventually had to just stop looking. Everywhere I turned, I found a new way a horror movie or show had used white deliberately.*

*It’s important to note that some colors that are more naturalistic, such as blue, green, and white, might appear onscreen just because it’s impossible to completely scrub them from the setting. So, if you’re setting something outside, unless you’re doing some serious color correction, there will always be a blue sky, green grass, and white clouds. However, for this and all other collages, I tried to use examples where the subject color was clearly a directorial choice, whether that was in set design, costuming, or camera tint. This is a point I should have probably made at the start of the series, but, hey, no time like the present.

Anyway, all of this is to say that horror creators clearly love to use white. And the more I thought about it, the more it made sense. If I had all these associations with white as a positive color, then of course horror was going to try to distort that. What is horror if not the perversion of that which we hold the most sacred?

So, since this is the final article, I’m going to do something a little bit different. Instead of only looking at how horror uses white, I’m going to take a look at how horror corrupts the positive associations of white. I want to explore how horror inverts our expectations of the color white. To do this, I’ll be taking a look at A Nightmare on Elm Street, Eraserhead, Get Out, Midsommar, Neon Demon, Psycho, The Invisible Man, Saw, Alien, Tanarive Due’s “Patient Zero” and “Like Daughter,” Misery, The Shining, and The Thing.

Expectation: White is Good (and Pure and Innocent); Black is Bad (and Evil and Corrupting)

Inversion: White is Terror and Alienation

If you Google “meaning of white,” the first answers you get are about how white symbolizes purity and innocence. There are some examples of horror movies capitalizing on this concept, such as the young girls who wear all white dresses in A Nightmare on Elm Street as they jump rope and sing the infamous jump rope song. However, most horror content is less interested in capitalizing on this association, and more interested on inverting it.

It’s easy enough to find positive and negative associations with both colors. White can be the blinding light of a deadly invader or it can be the mellow clouds of a summer day. Black can be the inky shadows of an urban sprawl or it can be goths. And honestly, what’s better than goths?

I covered this in my previous article about the meaning of black in horror, but there are also racist undertones to the assumption that black is darkness, evil, and suffering, white is always purity, innocence, and goodness. There are two sides to this: creators who build on this assumption and audiences that uncritically accept it as truth.

Jordan Peele’s Get Out directly confronts the “white as purity” stereotype to comment on race relations in modern society. Whiteness appears as overbearing and oppressive. If it is “pure,” it is self-consciously so.

Peele especially uses the character of Rose to first construct and then destroy a figure of white innocence. Rose is the white counterpart to the dark-skinned Chris, but during the beginning of the movie, she acts as his ally. When she transforms from loving girlfriend to predatory villain, her entire demeanor changes. She delves deeper into her identity as “white” (though, now no longer an ally but a usurper). Her transformation is physical, too. Her hair is pulled clinically back into a bun; she wears a crisp white button-down, and she is lit by the harsh white light of the computer. She embodies the white ideal that her family believes, “evoking ideas of purity and colonization.”

Similarly, 2019’s Midsommar explores the insidious nature of white supremacy. The film’s visuals are cottagecore set to 11, with the characters often donning light, breezy white cloth during their stay with the Hårga. The Hårga themselves seem almost obsessed with a “clean” whiteness, even in scenes when they are at their dirtiest. The infamous cliff jumping scene is characterized by a chalky white backdrop of rock that provides the perfect counterpoint to the bright red blood that will soon spatter it. We realize that the Hårga uphold whiteness as an ideal of purity and goodness. We realize that this belief goes deeper than just the color.

“As a red-cheeked and rotund Hårga woman explains to the assembled crowd in Swedish, the commune observes the maypole dance tradition during its midsommar festivities to spite “the Black One,” who, some time in the distant past, put a spell on the women that caused them to dance in a frenzy until they died. The explanation provides a rare glimpse into the cult’s dogma, and although this “Black One” is, presumably, an allusion to a devil or demon, it sounds particularly harsh and bigoted in the guttural Swedish of this white linen-clad milkmaid.”

Noor Al-Sibai, “In ‘Midsommar,’ Silent White Supremacy Shrieks Volumes”

Expectation: In Light, There is Safety

Inversion: In Light, There Is Nowhere to Hide

Horror movies, which often rely on shock as an emotion to evoke fear in an audience that has been inoculated to its trickery, often inverts our expectations. JP Ruz covers how Eraserhead uses its black and white cinematography to effectively invert audience expectations. The film establishes a language where white is good and black is evil by framing shadows as the “soothing places we want to crawl back to in escape of the shattering, terrifying whiteness.”

“The room was bright and white and still and silent, but soundless sound roared and howled in it.”

Anne Rivers Siddons, The House Next Door

Beyond its exploration of race relations, Midsommar uses white to invert our assumptions that the color, outside of racialized meaning, is one of innocence and safety. White becomes the costume of a cult. It is used to intentionally disarm outsiders. Midsommar also uses brightly lit sets, for the most part, inverting one of the most common horror tropes where we know that nighttime is dangerous and daylight is safety. Here, daylight is eternal; the danger happens in plain sight.

Expection: A Clean (White) Room is a Safe Room

Inversion: In Whiteness, We Are Vulnerable

Let me paint a quick mental picture:

Room A is a bathroom that has just been cleaned. The tiles shine; the ivory bathtub gleams; the vanilla scented candle flickers peacefully in the corner. The marble countertop and pearl sink sparkle. The overhead light has just been changed and you can see every corner of the room, where there is not a single speck of dust. There are fluffy white towels hanging on the towel rack, still warm from the dryer.

Room B is also a bathroom, but if anyone has ever cleaned it, it was long before you were born. The floor is sticky and there is a rust-colored stain in the bathtub. The soap scum in the sink has never been wiped away and forms a frothy crust. The lightbulb flickers, its palid glow a swan song. There is a single ratty towel dangling from a hook in the wall. When you touch it, it’s slightly damp.

Now, with that picture in mind: if you had to take a bath, which room would you choose?

Horror knows that it can make audiences uncomfortable by choosing dingy locations. Just look at Saw and the wave of horror grunge it inspired. My reaction to the bathroom in Saw is visceral. But it’s also worth noting that, while the bathroom in Saw is covered in floor-to-ceiling white tiles, the movie’s cinematography is so blue-tinted, that the bathroom doesn’t even look white.

That’s because Saw was going for a disgust reaction, building on the idea that white is color of cleanliness by showing us how easily it’s made dirty. It took a place traditionally kept clean and made it as disgusting as humanly possible. Saw said: hey, have you ever wanted to spend 90 minutes staring at a gas station bathroom? In doing this, Saw reinforces (rather than subverts) the idea that white is the color of cleanliness and, as a result, security.

There are, however, examples of the reverse, transforming all-white backdrops that are completely clean into sights of discomfort. Because white is such an unforgiving backdrop, where every blemish or divergence is loudly visible, it can be an incredibly vulnerable color. With white, there is nowhere to hide. The spotlight is on us. In Neon Demon, the color white is used deliberately in scenes when Jesse is at her most vulnerable: alone with a photographer who has intentions she cannot know, and in a room of underwear-clad models being assessed like pieces of meat.

“The idea of shooting this scene all in underwear, which is a true scenario, is that it makes everything pure meat,” explains Neon Demon Director Nicolas Winding Refn in Anatomy of a Scene. “And the idea is that you’re disposable and you’re degraded and you’re kind of looked upon as nothing but a prop.”

One of the places where we are at our most vulnerable is in the bathroom. It’s why Saw’s corruption of it feels like such an assault. The things that happen in the bathroom are private. Ever since Psycho, the bathroom has become a room distinctly associated with horror, particularly the shower. That’s because in the shower we are physically naked and symbolically exposed. Have you ever closed your eyes to wash shampoo out of your hair only to wonder if you’re about to be attacked by a shower demon?

Often, this vulnerability means that when characters are in the bathroom, they do not know how near danger lurks. The audience usually does, which adds an extra level of tension. The original A Nightmare on Elm Street features a famous bathtub scene where Nancy attempts to unwind amid the soapy white bubbles, unaware that Freddy’s claw has just broken the water’s surface. More recently, 2020’s The Invisible Man has protagonist Cecilia close her eyes in the shower, believing herself safe from the abusive grip of her husband, only to have an ominous handprint appear in the foggy white glass of the shower door. We see it first. We know that he is there, invisible, and we have no way to warn her.

Expectation: Trust The Lab Coat (White Means Knowledge and Health)

Inversion: Beware The Lab Coat (White Means Experimentation and Artificiality)

Combining its associations with sterility, cleanliness, and vulnerability, the color white is often associated with the medical field, especially (in horror) with medical experimentation. Nurses began wearing white in the early 1900s to indicate cleanliness; as mentioned, white is an unforgiving color. Every blotch shows.

Because white is the symbol of doctors, we come to see it as a beacon of knowledge, safety, and authority. And horror’s favorite thing to do with beacons of knowledge, safety, and authority is destroy them. The chestburster scene in Alien, while graphic, still uses white as its main color. The ship’s equipment is white; its crew wears white clothing. The clinical backdrop contrasts the harsh reality of what is about to happen to John Hurt. Tanarive Due’s “Patient Zero” uses the medical staff’s clothing to indicate the deteriorating state of the world outside its hospital setting:

“She is very neat and wears skirts and dresses, and everything about her is very clean except her shoes, which are dirty. Her shoes are supposed to be white, but whenever I see her standing outside of the glass, when she hasn’t put on her plastic suit yet, her shoes look brown and muddy.”

Tanarive Due, “Patient Zero”

As a result of its pristine unrealness, white can come to seem artificial. Alien abduction scenes are often characterised by a blinding white light. Tanarive Due’s “Like Daughter” aligns the themes of nostalgia and truth and the story’s core narrative about cloning with the characters’ surroundings:

“Denise’s living room was so pristine when I arrived, it was hard to believe it had witnessed a trauma… the walls were scrubbed white, and I could smell fresh lilac that might be artificial or real, couldn’t tell which. Denise’s house reminded me of the sitting room of the bed and breakfast I stayed in overnight during my last trip to London, simultaneously welcoming and wholly artificial. A perfect movie set, hurriedly dusted and freshened as soon as visitors were gone.”

Tanarive Due, “Like Daughter”

Expectation: The Snow Is Beautiful

Inversion: The Snow Is Deadly

“The snow was endless, a heavy blanket on the outdoors; it had a way about it. A beauty. But I knew that, like many things, beauty could be deceiving.”

Cambria Hebert, Whiteout

If you’re the main character in a Christmas movie, snow is probably a good thing. It probably signifies hope and beauty. It is probably received with a sense of childlike wonderment. If you’re the main character in a horror movie and it snows, good luck.

Snow, in horror, is almost invariably a sign that things are about to get much, much worse. The reason is simple: too much snowfall keeps us from being able to leave. And if where we are is currently infested with monsters and villains, well then not being able to leave is a pretty big problem. With its ability to strand people, snow transforms the color white into a symbol of isolation.

In a way, snow becomes a sort of antagonist, the catalyst for the characters’ isolation and, ultimately, a symbol for their seemingly endless suffering. In Misery, snow works in collaboration with Annie as Paul Sheldon’s jailer. By isolating characters, snow transforms them into their worst selves. In The Thing, snow helps generate the sense of claustrophobia that feeds the flame of paranoia already burning bright within its characters. The Shining uses a snowy labyrinth to represent the characters’ disorientation and feeling of being unable to escape evil.

White as the Color of Death

As a final note, while in Western cultures, the color of “death” is usually black, in many Eastern cultures, white is actually the color associated with death and mourning. In China, for example, white is the color of mourning. As another example, many Japanese ghosts wear white and have pale faces. Picture the ghost from The Grudge. As a result of this association, many non-Western movies (and even some Western movies) use white to represent death. However, I didn’t want to call it strictly “an inversion” because it’s just a different cultural system of values.

Besides, even in Western cultures, white is still associated with death. The phrase “white as a ghost” refers to the way fear drains the color from your face. Often, ghosts in movies or books are represented as amorphous white glimmers. There is the pervasive (though not necessarily true) belief that our hair can turn white from fright, which the Twin Peaks TV show uses to represent rapid character change. And, of course, the most popular funeral flower is the white lily.

“The calla lilies are in bloom again. Such a strange flower, suitable to any occasion. I carried them on my wedding day, and now I place them here in memory of something that has died.”

Katherine Hepburn as Terry Randall, Stage Door

***

In a nutshell: In horror, white can symbolize deadlines, a cult-like mentality, hidden danger, vulnerability, medical experimentation, alien abduction, artificiality, isolation, death, and profound fright

Contrasts….loved that you tackled white as a shade used in horror!!!! Enlightening!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks!!

LikeLike