“Most people have a certain understanding of what a horror film is, namely, that it is emotionally juvenile, ignorant, supremely non-intellectual and dumb. Basically stupid. But I think of horror films as art, as films of confrontation… Just because you’re making a horror film doesn’t mean you can’t make an artful film. Tell me the difference between someone’s favourite horror film and someone else’s favourite art film. There really isn’t any. Emotions, imagery, intellect, your own sense of self.”

David Cronenberg

Anyone who’s a fan of the superhero genre (or has seen a single blockbuster film in the last decade) is probably a little burnt out on “wink at the camera” humor. You know the kind of writing I’m talking about: an allergy to earnestness, serious conflict undercut by banter, stage four irony poisoning. “He’s behind me, isn’t he?”

If I had to define this style of moviemaking in a single word, that word would be “self-conscious.” It almost feels like these movies are embarrassed to be superhero movies in the first place. Rousing speeches are cut short if not entirely replaced by quips; the costumes are all dark and serious (no spandex in sight). With these aesthetic changes, there has also been a gradual shift away from the core of what these stories stood for: a battle between good and evil, a dedication to doing what’s right even when what’s right isn’t easy. Martin Scorsese controversially described this recent wave of superhero films as not cinema but spectacle, a digital theme park, an assessment that feels harsh but a little true. These movies redefined the language of their genre, to the point that it’s rare that a good, serious superhero movie makes it onto the silver screen. (Looking at my beloved Spiderverse films as the light in the darkness.)

Like superhero flicks, the horror genre doesn’t often get much critical acclaim. When you’re creating something that’s part of a genre like this, beloved by fans and side-eyed by tastemakers, it can be easy to feel self-conscious. The larger your audience, the more you open yourself up to criticism, especially if what your genre calls for is exactly the kind of thing that people point to and say, “See? That’s why no one takes you seriously.” When I went to see Maxxxine in cinemas, I was struck by how very un-self-conscious it was. The third movie in a (semi-unplanned) series, a slasher, a sex romp: it had a lot of things stacked against it (if it was trying to be a respectable film). But it didn’t shy away from itself. In fact, it was a movie that knew exactly what it was and was perfectly content to be so. In that sense, it reminded me of Tremors, which I’d only watched a few nights prior. Though very different in style and substance, both movies showed incredible awareness of their own genre with little interest in subverting it. They were perfect specimens of what I now think of as a self-aware movie.

What is a self-aware movie?

Overall, the self-aware movie is defined by the following three characteristics:

1. The self-aware movie is a love letter to its genre

What separates a self-aware movie from just a great movie within a genre is its awareness. Often, this manifests as the movie being both of and about the same thing. Take as an example Singing in the Rain, a movie musical about a movie musical.

Self-aware movies match the genre that they love. They explicitly express expected themes, character archetypes, or plots. After all, it’s what these kind of stories do. Think of the detective fiction of Agatha Christie which creates its own internal language of place (a large house, rich, in the countryside), characters (a social melting pot of classes, skewing towards aristocratic), and stakes (closed-room murder where the suspect must be in the room as we speak). You know it’s a Christie the entire time that you’re reading it.

2. The self-aware movie is unseriously serious

Awareness in the act of creation requires a sense of humor. If you’re too aware that you’re making a movie, and you take yourself too seriously, then you either end up maudlin or irreverent (see: self-conscious). The self-aware movie is tongue-in-cheek. It is not afraid of silliness or banality; it revels in them. However, importantly, for the characters in the movie, the plot is serious. They may act bombastic or camp, but their approach is wholly earnest.

A great example of this is the general career of Arnold Schwarzenegger. Known for his one-liners, ridiculous stunts, and generally over-the-top performances, something key to the charm of Schwarzenegger’s characters is that you still believe that they believe their schtick. They make you laugh, but they’re not entirely comedic figures. Specifically, Last Action Hero is a perfect emblem of the self-aware movie: it’s an action movie about action movies. While a lot of the comedy derives from the “action movie world” being exactly like you’d expect the action movie world to be, Last Action Hero never makes fun of the audience for liking action movies. It likes action movies; if it didn’t, why would it exist?

3. Despite its unseriousness, the characters and plot are played straight

The characters in a self-aware movie don’t know that they’re in a movie. They react to plot beats like they are events in their lives. The victim in a self-aware horror film is still afraid of dying because she still values her life. The circumstances might be bombastic; the killer might be wearing a ridiculous mask; but the stakes, for the character, are dead serious.

In its approach to plot and story, the self-aware movie also differentiates itself from satire, or, G-d forbid, parody. It doesn’t seek to subvert convention, or highlight flaws in the genre, but, instead, plays it straight. Scream is the quintessential self-aware horror movie. The characters explicitly allude to horror movie tropes, but it also is literally a horror movie that abides by these tropes. Compare that to its companion, Scary Movie, which as a parody is a (weak) comedy before it’s a horror movie, and you’ll see the difference.

Let me tell you what you’re in for: how the self-aware horror movie operates

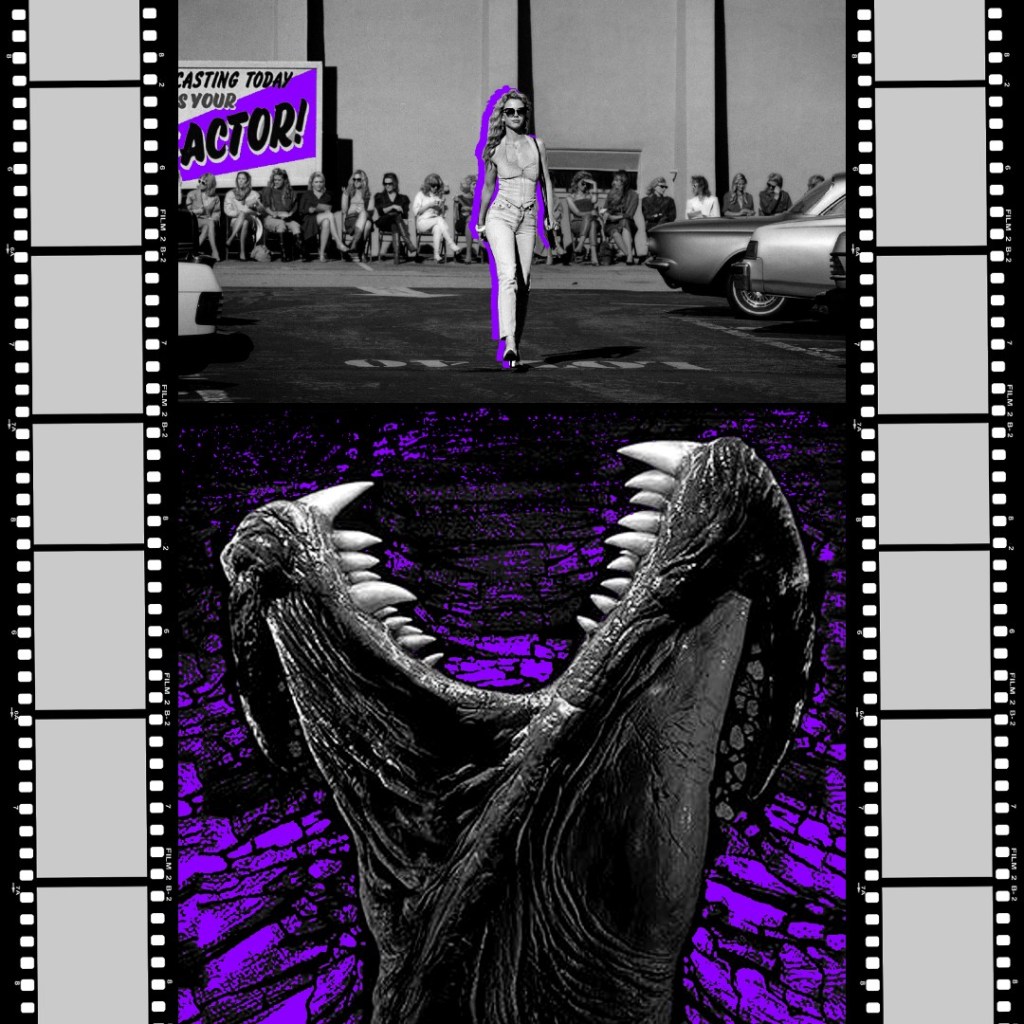

MaXXXine and Tremors tell you exactly what you’re in for from their very titles.

Tremors has a double meaning. There’s the literal seismographic event it refers to that summarizes the movie’s plot about subterranean creatures. But then there’s the other, slightly more silly reference to the trembling that a scary movie might produce in an audience. It’s this kind of attitude that makes Tremors self-aware. I mean, just look at the poster:

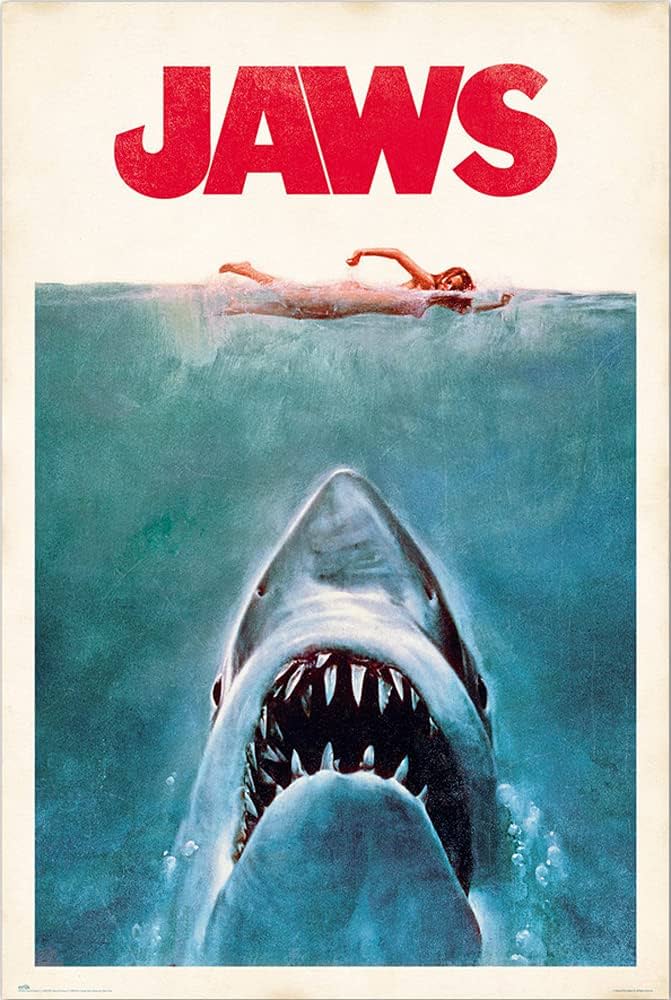

It’s not that it’s trying to parody Jaws, the monster flick that created the concept of the summer blockbuster. It’s just honoring its predecessors. It knows it comes from a long history of B-movie monster flicks and it intends to honor that legacy.

The plot of Tremors is deceptively simple. It explicitly lays out the stakes: here are the relevant players, these are the monster’s powers and how they are summoned, here are the sets for future set pieces. As Darren explains in Non-Review Review: Tremors, “Ron Underwood’s film adheres relatively faithfully to the genre conventions we’ve come to expect. The characters are still trapped by the plot in a confined location, with circumstance and plot contrivance conspiring to keep our two plucky heroes in the region, against their desire to leave. “I mean, is there some higher force at work here?” Earl Basset loudly laments when bad luck continues to ensure that he and his partner Val are unable to depart their desert community despite several attempts.”

Meanwhile, MaXXXine’s title explicitly points to its sexploitation origins (the triple X serving a dual purpose of telling you what number in the series this movie is). Where Tremors uses establishing shots of the town, its locations, and its residents to clearly lay out the geography of what the characters will be working with later, when the monster comes to town, MaXXXine leans upon its genre conventions to let you know what you’re in for. It uses the device of Maxine herself filming a horror movie, The Puritan II, to let you know what it thinks about horror movies. As the director of The Puritan II explains to Maxine: she’s making a “B movie with A movie ideas”.

Is horror a serious genre?

Point in favor: yes, it’s obviously a serious genre. It deals with some of the most serious topics that exist: death, fear, suffering.

Point against: no, it’s not. Because it doesn’t take those serious topics seriously. They’re exaggerated, dramatized. Disrespected even. You need look no further than Thanksgiving, where a woman dies after being dressed as a turkey and baked in an oven at 450 F until crispy and golden brown.

Counterpoint: Sure, there are unserious parts of horror, but you can’t paint it all with the same brush. After all, horror also houses films like Jordan Peel’s Get Out, a thoughtful depiction of racial tensions in America. The answer is simple: bad horror is unserious and good horror is serious.

Since the 2010s, a wave of artistic horror has become known and loved by mainstream audiences that traditionally eschew the genre. In Post-Horror: Art, Genre and Cultural Elevation, David Church seeks to find a good term to refer to those kinds of movies: “Variously dubbed ‘slow horror,’ ‘smart horror’, ‘indie horror’ , ‘prestige horror,’ and ‘elevated horror’, films such as It Follows (2014), The Witch, It Comes at Night (2017), and Hereditary (2018) all emerged from the crucible of major film festivals like Sundance and Toronto with significant critical buzz for supposedly transcending the horror genre’s oft-presumed lowbrow status, and succeeding in crossing over to multiplexes.”

So, what we see then, as these movies enter the mainstream, is the creation of a hierarchy of horror. At the bottom, you have cheesy slashers named things like Buckets of Blood VI: Off the Handle, which is low art and not valuable. And rising to the top, you have prestige art films that actually stand with critics, titled something like It is Afraid. These “good” movies often feature long, slow shots, realistic dialogue, and limited jump scares (those cheap thrills that ruin the moviegoing experience). They are often praised for “subverting” the archetypes of their genre. What’s unique about these movies is they reach both horror lovers and horror haters, or as Church deems the audiences: horror-friendly and horror-skeptic.

The most extreme horror-skeptic might even be tempted to free these “good horror movies” from the shackles of the genre, arguing they aren’t horror at all. Horror, in their eyes, is an inherently unserious genre. This horror-skepticism runs so deep that it even affects the creators of these works. Many writers and directors of some of the most beloved horror classics distance themselves from the genre. Director Jennifer Kent said of The Babadook, “I didn’t think about genre… and I certainly didn’t think of it as a horror film.” Trey Edward Shults claimed that he didn’t “set out to make a horror movie” when he made It Comes at Night, Jordan Peele consistently referred to Get Out as a social thriller in promo materials, and Ari Aster calls Hereditary “a family tragedy that curdles into nightmare.” Even William Friedkin stated that he didn’t “set out to make a horror movie” when talking about The Exorcist, a film you would be hard-pressed to call anything but horror.

What’s refreshing, then, about Tremors and MaXXXine as self-aware horror movies, is that they don’t seem embarrassed to be horror films. In fact, they revel in it.

Slashers and creature features: schlock and proud

“In recent years, the term ‘elevated horror’ has been used by film fans online to describe the new trend of thought-provoking, arthouse horror films from independent studios like A24… But to use the term elevated horror, which is to imply that these films are “above” what horror normally offers, feels incredibly disingenuous and is frankly disrespectful to the history of the genre. The term does not recognize how many successful modern horror films succeed due to their use of the conventions and tropes of the genre.”

Matt Minton, Column: Horror is a genre worthy of your respect

I have a particular pet peeve about when people try to explain that a horror movie is good by telling you that it doesn’t rely on jump scares. Now, don’t get me wrong. I’ve watched my fair share of films that rely too much on jump scares, ones that only terrify you in the moment of watching and then dissolve into memory the second you stop watching. Those movies have their purpose (they are excellent sleepover fodder), but I understand why they seem less intentional. However, I hate the concept that good horror movies don’t have jump scares. Jump scares are one of the many tools in the horror toolbox. They serve a purpose. They engage you; they draw your attention. They scare you. But they’re also associated with schlock, with cheap thrills and low brow entertainment.

What’s refreshing about Tremors and MaXXXine is that they both draw upon the lowest of the low: the creature feature and the slasher. In Men, Women, and Chain Saws: Gender in the Modern Horror Film, Carol J Clover describes the public’s conception of slashers as being “at the bottom of the horror heap.” They are “drenched in taboo” and teeter on the edge of “pornographic”: “the slasher film lies, by and large, beyond the purview of the respectable (middle-aged, middle class) audience.” Creature features are also rarely considered high art, the very term we use to describe them being both twee and dismissive. The world’s conception of Godzilla, for example, leans towards bombastic, over-the-top, and silly, whereas the original 1954 movie is a sombre exploration of post-nuclear Japan. The lack of respectability in these genres gives power to the way that Tremors and MaXXXine lavish in them.

“Straining to be respectable not only misjudges the nature of the genre; it robs us of one of the most potent scares you can have at the theater: the horror of realizing you love horror.”

Jason Zinnoman, Part I: Stop Trying To Be So Respectable

Slashers and sexploitation films in particular get a bad rap for being inherently anti-woman. The logic behind this label is this: they are movies centred on the desecration of the female body, presumably for the pleasure of a male audience. But MaXXXine rejects this label, the plot of the entire trilogy it’s a part of hinging on the ambition of its female protagonist. At the same time, the movie isn’t subverting the genre it is in; Maxine is still a sex worker completely comfortable with nudity. Sex and violence drench the entire trilogy. But Maxine, despite being pursued by a mysterious force, is not a disempowered character. When a man stalks her down an alleyway, thinking he’s secure in cornering a woman alone in the dark, Maxine turns the tables. It is he who ends up naked, humiliated, and grievously injured. In a violent world, Maxine is up to the task:

“Tabby Martin: Be careful out there.

Maxine Minx: I can handle myself.

Tabby Martin: So said every dead girl in Hollywood.”

I think that the explanation of slashers as being watched by men and exploitative of women is oversimplified and doesn’t account for their actual audience. In talking about horror as a genre, Isabel Cristina Pinedo explains that this assumption of a “sadistic male” audience “leaves now room for the pleasure of female viewers, particularly feminists, except as masochists or sex traitors.” Exploitation films can provide a fertile ground to reclaim a genre, and to explore taboo concepts. In MaXXXine, The Puritan II, a horror sequel that Maxine is slated to start in, is being picketed by adults swept up in the satanic panic of the 1980s. While society at large is no longer particularly concerned about secret satanic blood cults infiltrating D&D games, the puritanical (pun intended) view of sexuality and nudity remains strong.

“There’s a certain freedom too which horror allows. It’s the freedom to really push boundaries and creatively express yourself. It allows a film-maker to almost re-invent cinematic rules. You can push the limits of logical reality with your cinematography. You can do things which are a little odd perhaps. A blue light that has no logical output? What the hey!”

Tom Jollifee. It’s Time to Give the Horror Genre More Respect

The thing about MaXXXine and Tremors is that despite their pride in genres that are widely considered shameful, they aren’t vapid movies. The staying power of Tremors is apparent not only in the amount of sequels it spawned (did you know the Graboids have made their way to the icy north now?), but in its status as a cult classic. At its core, Tremors is the archetype of a classic storytelling conflict: man versus nature. It is a battle between the self and the world it inhabits. The characters are imperfect yet wholly themselves; their triumph at the end feels like a triumph for humanity at large.

It’s actually legal for horror movies to be fun

“In short, for nonplussed viewers, both casual and professional, [elevated horror movies] may be stylish, moody, and technically accomplished – but they are not conventionally “fun”

David Church, Post-Horror: Art, Genre and Cultural Elevation

Both Tremors and Maxxxine are incredibly fun to watch, a fact that constitutes about 40% of why I enjoyed them. They’re movies that feel like everyone involved in making them had a good time: the sets are impeccable and perfectly suited for their environments, the costuming exact, the writing delightful, and the acting energetic.

Tremors goes so far as to toy with its audience by creatively devising new ways to create loud, consistent thumping sounds on the ground. It’s vibrations in the ground that summon the movie’s creatures, so we are treated to everything from broken generators to bouncing basketballs, from rattling trucks to pogo sticks. With every rattle we tense, awaiting the inevitable presence of sharp teeth and a gaping mouth.

“The whole point of Camp is to dethrone the serious. Camp is playful, antiserious. More precisely, Camp involves a new, more complex relation to ‘the serious’. One can be serious about the frivolous, frivolous about the serious.”

Susan Sontag, Notes on Camp

MaXXXine uses the backdrop of real events, from the satanic panic to the months of terror when the Night Stalker terrorized LA, to tell a story that is unserious and dramatic. In a critique of Maxxxine, Chirsty Lemire states, “it’s a crushing disappointment. The style remains firmly in place – this time, it’s a lurid look at Los Angeles in the mid-1980s – but there’s nothing underneath it.” That feeling of emptiness, I think, is actually part of its appeal. It’s not that it’s all style and no substance: it’s that the style is a large part of the substance.

In Billy Russel’s review of Tremors, he says “I tend to think of Tremors as being just about the perfect monster movie. I don’t think it’s Citizen Kane, obviously, but as far as monster movies go, you just can’t do any better than Tremors.” I agree, but I would take it even one step further. I wouldn’t even bother comparing Tremors to Citizen Kane. Citizen Kane is a great movie, and so is Tremors. I’m glad they both exist. The best trashy nachos you’ve ever had aren’t inherently worse than the best steak. They feed a different hunger.

“Books are fun. Reading is fun. The world of literature is not an exclusive club that you ascend through by having read the right books, and in a world where reading as a pastime is diminishing, and where bookshops are struggling, such a view-point is poisonous and backward.”

Jon Oliver, High Brow, Low Brow, No Brow

Kevin Bacon gets it

Kevin Bacon gets it. He’s in both Tremors and MaXXXine, a fact I only realized after I began to write this piece. But I think his approach to both movies serves as a perfect crystalization of what it means to be a self-aware movie. His acting in both films is over-the-top, certainly not naturalistic, but also never making fun of its audience. It’s perfectly suited to its environment. In Tremors, he’s Val, a charismatic fuckup with a laundry list of requirements for any potential lover. He’s silly and fumbling; he’s baloney and beans, an everyman in double denim. When he kills one of the Graboids (not called Graboids, actually, until the second film in the series, before some nerd tries to correct me in the comments), his immediate reaction is to yell “FUCK YOU” and laugh in its dripping face. Not long after that, he’s out trying to sell the corpse for parts.

Then there’s his portrayal of John Labat in MaXXXine, a gold-toothed slimy private eye for hire who sounds like he was just left out to dry a week ago. His accent is perfect, his mannerisms excessive. The character, like Val, is a little silly, and yet his approach to playing John is serious. He did deep research to create John Labat. Overall, Bacon plays these roles straight, frequently showcasing how much he likes and respects the horror genre.

***

The self-aware movie, above all, lacks shame. Where the self-concious movie is constantly looking over its shoulder to check whether the audience is laughing at it or with it, the self-aware movie looks straight ahead with its head held high. This isn’t to say that the self-aware movie doesn’t care about its audience. It loves its audience; its audience’s love of movies like it is its raison d’etre.

What I like about the self-aware movie is how it lovingly takes its audience by the hand and asks us to reflect on the genre it inhabits. It acts as part love letter, part mirror. Movies like MaXXXine or Tremors inspire tenderness in me, reminding me what I love about the genre they inhabit, unafraid to be ridiculous, bombastic, or wonderfully distant from anything resembling respectability.

“Wayne: Now, I may not know shit from shinola when it comes to filmmaking, but I know for damn sure people are gonna wanna see what I just saw in there.

RJ: Well, that’s ’cause I’m not treatin’ it like pornography, but as cinema. That’s what these other adult films are lackin’.

Wayne: Whatever you’re doin’, you keep doin’ it. People’s eyes are gonna pop out of their damn skulls when they see this. We’re gonna be rich! Feel how hard my cock is!”

Ti West, X

1 comment ›